Carceral Visuality

This study guide introduces artworks and artists that engage with issues of carceral visuality. It contains a brief definition of “carceral visuality,”” followed by a summary of how some of the artists invite reflection on the relationships between the United States carceral system, vision, and power. Relevant short clips from artist interviews are included within each section, and the embedded links will take you to more information about the artworks and artists mentioned.

What is Carceral Visuality?

“The history of visuality linked to the prison is a main reinforcement of the institution of the prison as a naturalized part of our social landscape.” ~Gina Dent

“I think of policing as a way of seeing and a sort of visual frame that recognizes people through different lenses such as guilty or criminal or as targets.” ~American Artist

To paraphrase visual culture theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff, we make sense of what we see through what we already know and have experienced. Our societies, belief systems, families, education, and many other social and political conditions inform how we see and how we understand what we see. As American Artist alludes to, in the quote about policing above, within our “ways of seeing” there are forms of power, narratives, and ideologies that work on our senses. The term “visuality” refers to this relation between seeing, knowing, visual representation, and power. It also refers to the structures that inform how we see and determine who has the right to look, where, and at what, as well as who has the power to choose who and what is visible.

“Carceral” is a verb that describes anything related to jails and prisons, so “carceral visuality” is the form of visual power embedded in the system of prisons and policing. It is how our social relations that are constructed through policing, prison, and jails impacts how we see the world around us. One example of carceral visuality given by Mirzoeff is when you approach the site of an accident and the police tell you, “Move along, there’s nothing to see here.” In that moment, the police are controlling what you are allowed to see. But carceral visuality also refers to the variety of ways our perceptions have been shaped by the idea and practices of imprisonment—even for people who do not see themselves as connected to or affected by incarceration.

This study guide asks two main questions about carceral visuality:

- How does the nexus of prisons and policing affect how we see each other?

- In what ways is the carceral state both visible and invisible within our current systems?

How does the system of prisons and policing affect our vision of ourselves and each other?

“Visuality’s first domains were the slave plantation, monitored by the surveillance of the overseer, operating as surrogate of the sovereign.” ~ Nicholas Mirzoeff

“Racism and anti-Blackness undergird and sustain the intersecting surveillances of the present.” ~Simone Browne

Slavery: The Prison Industrial Complex, 1980

Who’s That Man on the Horse, I Don’t Know But They Call Him Boss

Keith Calhoun

Nicholas Mirzeoff posits that the slave plantation is the original site of disciplinary surveillance and where current regimes of carceral visuality emerged. This connection is made chillingly present in Keith Calhoun’s photograph Who’s That Man on the Horse, I Don’t Know But They Call Him Boss, 1980.

The image, taken 115 years after the abolition of slavery, shows a White prison guard on a horse who is watching over hundreds of incarcerated men, the vast majority of whom are Black. The gaze of the prison guard is an exercise of power in the same explicit as the rifle he holds or his elevated presence on the horse. Not only does this photograph depict the labor exploitation and racialized hierarchies that persist in the United States, as discussed in the Histories & Structures guide, it also illustrates the ongoing role of visuality within these power structures.

What we are calling “carceral visuality” is similar to what Simone Browne calls “surveillance.”” According to Browne, “surveillance” often operates along racial lines, making racial categories seem solid and, “the outcome of this is often discriminatory and violent treatment.” In other words, surveillance produces and reproduces our society’s ideas about race. Several artists in Barring Freedom consider the racializing and violent effects of hypervisibility and surveillance.

Jumpsuit Project

Sherrill Roland

Sherrill Roland’s performance The Jumpsuit Project, which he performs in public locations wearing an orange jumpsuit, highlights the hypervisibility of incarcerated individuals.

In the video below, he discusses the oppressive surveillance of his activities while in prison and the stigma of appearing in public as a Black man wearing an orange jumpsuit, which is reminiscent of his prison uniform. He refers to the jumpsuit as an illusion that clouds other people’s perceptions of him. Scholar Nicole Fleetwood states, “In the context of prisons, visuality functions to keep the imprisoned stigmatized as criminals who are excluded from realms of the intimate, social, and political.” Roland’s artworks speak to the discomfort of living within this visual regime.

Artist Dread Scott has three works in Barring Freedom, all of which address the repeated and ongoing policing of Black people in the U.S., particularly in low-income neighborhoods.

In the video installation STOP (2012), viewers are confronted by life-size projections of six men, who each take turns stating how many times they have been stopped by the police. The project is the result of a collaboration between Scott and British artist Joanne Kushner. The men on one side of the projection are residents of Liverpool, UK and those on the other are from Brooklyn, NY, pointing to the export of the U.S. “tough on crime” policing strategies. The number of police stops the men have experienced range from 30 to 200. As the men repeat these numbers, the video conjures the incessant nature of police discrimination and racism.

2018

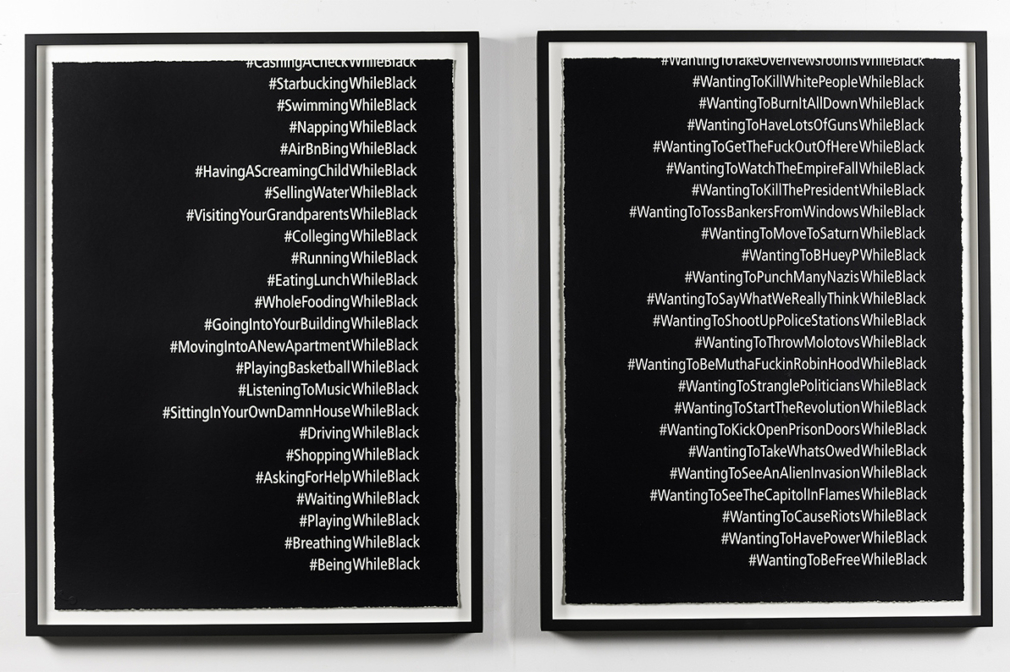

#WhileBlack

Dread Scott

Using a similar strategy of repetition, Scott’s print #WhileBlack lists many seemingly harmless activities that Black individuals have been policed and, in some cases, killed for performing.

The accompanying #WhileWhite provides a list of privileges that White individuals in the United States have been entitled to. As Mirzeoff states, “To be white is simply to be allowed to act.” You can see Scott discuss #WhileBlack on his artist page.

American Artist also explores police violence and racial profiling in his work.

Artist’s videos and sculptures critique the racialized biases of the technologies used in policing as well as the Blue Lives Matter movement, which was started by police officers in response to Black Lives Matter activism. His work resonates with Jackie Wang’s research into predictive policing. Wang states, “Whether it is a covert municipal financial structure that authorizes plunder or an algorithm that generates hot spots on a map, invisible forms of power are circulating all around us, circumscribing and sorting us into invisible cells that confine us sometimes without our knowing.” In the video below, American Artist discusses the troubling identity of blueness and how policing acts as a way of seeing, separating, classifying, and judging individuals.

In what ways is the carceral system visible and invisible?

“The carceral state is everywhere.” ~Maria Gaspar

“The more that prisons and jails are used as the solution to every social problem that our society doesn’t want to have to deal with, we see a desire to erase that.” ~Ashley Hunt

In California, the Department of Corrections employs more than 60,000 people and has an annual budget of over 14.9 billion dollars. The carceral state and its effects are indeed everywhere, but the scope of this power is not always visible. In her book, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California, which explores prison expansion in California, Ruth Wilson Gilmore points out that although prisons and detention centers are often located in rural or marginal spaces, “this apparent marginality is a trick of perspective.”

She argues that prisons play a key role in the political economy of California, even as they remain out of sight for many Californians. Along similar lines, writer and documentarian Brett Story argues that the expansion of the prison system since the 1970s is a fundamental facet in the rise of neoliberalism. Rather than a shrinking of state power, Story notes, “The carceral state is a state restructured and expanded through its punishment and criminalization functions.” Artists in Barring Freedom consider this tension between the presence and absence of the prison system in our physical and mental worlds.

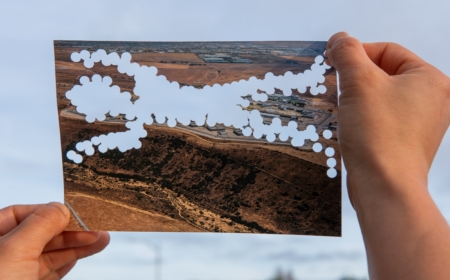

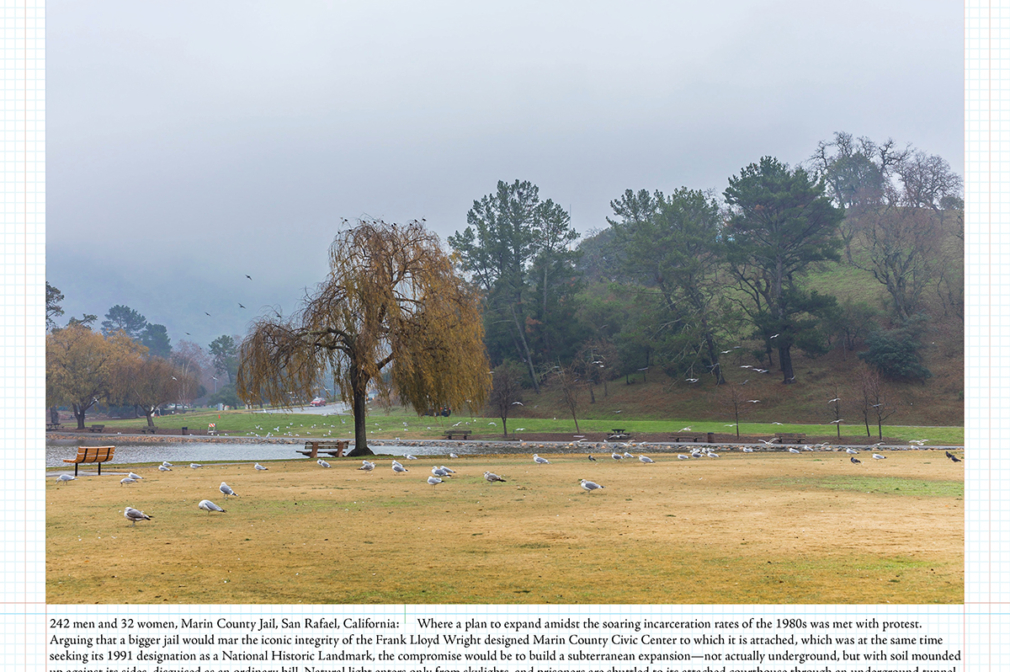

Marin County Jail, San Rafael, California, 2013

242 men and 32 women,

Ashley Hunt

In the series Degrees of Visibility, Ashley Hunt photographs detention centers, prisons, and jails from public locations. Most of of the images in the collection are unremarkable scenes, either of empty fields or of banal urban architecture. Were it not for Hunt’s titles, which name the prison and give the number of individuals incarcerated within, a viewer might not know that these facilities exist.

As Hunt discusses in the video below, this invisibility and the erasure of the prisons from our field of vision is precisely the point. He suggests that these forms of erasure both obscure and normalize the use of incarceration as a solution for social problems, such as poverty, mental illness, and unemployment.

Maria Gaspar’s immersive sound and video installation On the Border of What is Formless and Monstrous, focuses our attention on the massive concrete north wall of Cook County Jail in Chicago.

Far from invisible, this wall is a looming presence in the surrounding communities. In the video below Gaspar expands upon how the installation interrogates the wall itself. What does it hide from view? How does this wall distort how people on the outside view people within? Gaspar includes recorded sound from inside and outside the prison, blending the two into a single soundscape that allows the wall to become momentarily porous.

(A trailer of the video is available here).

Cited Readings

- Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. Penguin Books, 1972.

- Browne, Simone. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. “Budget Information.”

- Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2020.

- Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. American Crossroads 21. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. The Appearance of Black Lives Matter | NAME. Ebook., 2017. .

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas, How We See the World. Basic Books, 2016.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

- Story, Brett. Prison Land: Mapping Carceral Power across Neoliberal America. Illustrated Edition. Minneapolis: Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2019.

- Wang, Jackie. Carceral Capitalism. Semiotext(e) Intervention Series 21. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotexte, 2018.